The "symmetric" is a particular case of the "inverse", in which each note of one hand corresponds to a specific note/key in the other hand. This is possible in the piano, thanks to the peculiar configuration of the keyboard, which determines its own “topography”: long/low (white) and short/high (black) keys. In turn, black keys appear forming groups of 2 and 3 alternately.

On the keyboard there are two “symmetry axes”. One is a white key and the other a black key. Such keys that act as if they were "hinges", do so as if the keyboard could fold on themselves thanks to them, making the same movement that is done when a book is closed that is open on a table. That is, matching both parties in half. On the keyboard it would be to coincide imaginarily the left half with the right with each other. These two keys are: "D" and "G#/Ab".

Image 1 shows the correspondences of keys/notes between both hands when the note “D” is taken as a symmetry axis, and in image 2 when the note “G#/Ab” is taken as axis.

In image 3 two examples appear with each axis of two basic designs placed in the right hand and obtaining their corresponding symmetrical in the left hand. The fingering placed in the center of the staff serves for both hands, since being our hands symmetric with each other, we can match its own symmetry with that of the mentioned characteristic of the keyboard.

The

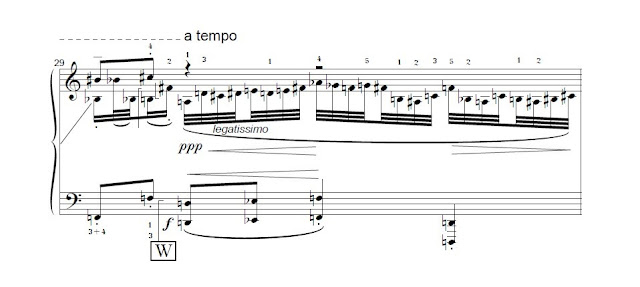

first time I used a "symmetrical" was in my op. 11, "Invention",

in 1990. As can be seen in the image shown below, in the second beat of the measure

29, a new motive arises in the right hand in thirty-second notes in pianissimo. Of this motive, in

the compass 39 its symmetrical appears in the left hand:

Since then I have used the symmetrical procedure to solve technical problems of piano execution of the left hand. When I have encountered a passage of considerable difficulty in the left hand, I have obtained its corresponding symmetrical in the right hand, to ask how she would fix them to make this passage, presupposing that she would do it more easily. I have observed and pay attention to the sensations and movements of the right hand, which has normally resolved such a passage with greater naturalness, relaxation and less devices and media deployment. Then I have tried, playing with both hands, the left with the original motive and the right with its corresponding symmetrical, that the left hand is infected from the same sensations of the right, simplifying their movements and obtaining greater relaxation. It is like a way to make the right hand teaches to the left how to play. Generalizing, it is also like trying to make the left hand compensate for its natural awkwardness with the greatest skill of the right hand. Throughout my encyclopedia I have usually used this procedure to achieve that balance between both hands.